New England Moldmaker Does It The Hard Way

This mold and die shop owner had a decision to make: build more capacity, or examine ways to make more finished molds out of existing capacity, save one new machine. He chose the latter.

Share

New England Mold (Sterling, Massachusetts) specializes in deep multi-cavity precision molds, using innovative approaches to automatic unscrewing molds, side-action and cam-actuated molds, and hot runner molds. Typical customers include medical, cap and closure, cosmetic, and automotive, and as often as not, New England Mold is in the loop from part design through prototyping and into production. And, as the company’s reputation attracts new customers, its current list of customers is constantly coming up with new products and new packaging designs, keeping both New England Mold plants busy 24 hours per day. Being so occupied led Jeffrey Barhoff, New England’s president, to have to make a decision: build more capacity, or examine ways to make more finished molds out of existing capacity, save one new machine. He chose the latter.

“We knew we had to be prepared for change,” he says, “but we wanted whatever we did to complement our electrode and wire EDM work coupled with surface grinding. We also knew that a super high-speed milling approach could take us directly to steel as well as cut electrodes.”

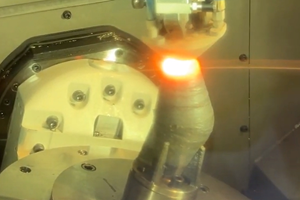

After careful consideration, Mr. Barhoff decided to go with the FMC Vibra-Free vertical machining center from Compumachine Inc. (Wilmington, Massachusetts). It is fairly similar to a small handful of other high-speed verticals that are changing mold and diemaking strategies through the adoption of hard milling techniques and elimination of manufacturing steps. The Vibra-Free’s rigid and thermally stable castings support a custom-Swiss-built IBAG high-frequency spindle capable of 42,000 rpm mounted on a bridge-type column above a 26.65 inch by 17.72 inch table. The machine is controlled by an advanced Fanuc 16i-MA CNC incorporating NURBS programming and high-speed algorithms for look-aheads.

The machine has had positive effects so far, according to Mr. Barhoff. One example is a complex mold with many round features that is destined to produce surgical suite pipette trays. “We cut this out of steel in the same time it would have taken to cut the graphite electrode,” he says.

In fact, the machine had work from the very beginning, tackling a variety of SS 48/50 Rc and S-7 54/50 Rc jobs as well as some electrode work. On the jobs in steel, Mr. Barhoff conservatively guesses New England Mold saved 50 percent of that particular portion of “the build” by simply taking the electrode step out of the picture, and allows that as far as electrodes are concerned, “you have to relearn how to cut them, and you have to be set up for it.” The molds went straight to the Brown & Sharpe Gage 2000 CMM and indicated within 0.0002 inch of specification, well within tolerance. And while many claim that the very small light cuts typical of HSM often eliminate the need for polishing, Mr. Barhoff is less enthused, probably because of the mirror-like finishes required of his molds. However, he does note that “I’d rather polish a milled surface than one that’s been burned.”

Mr. Barhoff says another area requiring study in HSM is the economics of the tooling. The tiny SKI 25 carbide coated tools (the cutter and toolholder fit in the palm of the hand) are not inexpensive—the toolholder is, of course, balanced—and their life and cost must be factored in when going straight to hard steel. A critical factor to tool life is often length to diameter, variable by speeds, feeds, and of course, materials.

Typically, though, hard materials in the range of RC40 are attacked with 1.0 mm to 1.5 mm carbide coated ballnose end mills turning between 30,000 and 40,000 rpm and fed at between 90 and 100 ipm. Graphite, on the other hand, is nominally machined with flat end mills, when possible, often with larger diameters, and speeds in the 25,000 rpm range and feeds of about 50 to 60 ipm. MMS

Related Content

In Moldmaking, Mantle Process Addresses Lead Time and Talent Pool

A new process delivered through what looks like a standard machining center promises to streamline machining of injection mold cores and cavities and even answer the declining availability of toolmakers.

Read MoreHow a Custom ERP System Drives Automation in Large-Format Machining

Part of Major Tool’s 52,000 square-foot building expansion includes the installation of this new Waldrich Coburg Taurus 30 vertical machining center.

Read MoreTsugami Lathe, Vertical Machining Center Boost Machining Efficiency

IMTS 2024: Tsugami America showcases a multifunction sliding headstock lathe with a B-axis tool spindle, as well as a universal vertical machining center for rapid facing, drilling and tapping.

Read MoreAdditive/Subtractive Hybrid CNC Machine Tools Continue to Make Gains (Includes Video)

The hybrid machine tool is an idea that continues to advance. Two important developments of recent years expand the possibilities for this platform.

Read MoreRead Next

AMRs Are Moving Into Manufacturing: 4 Considerations for Implementation

AMRs can provide a flexible, easy-to-use automation platform so long as manufacturers choose a suitable task and prepare their facilities.

Read MoreLast Chance! 2025 Top Shops Benchmarking Survey Still Open Through April 30

Don’t miss out! 91ÊÓƵÍøÕ¾ÎÛ's Top Shops Benchmarking Survey is still open — but not for long. This is your last chance to a receive free, customized benchmarking report that includes actionable feedback across several shopfloor and business metrics.

Read MoreMachine Shop MBA

Making Chips and 91ÊÓƵÍøÕ¾ÎÛ are teaming up for a new podcast series called Machine Shop MBA—designed to help manufacturers measure their success against the industry’s best. Through the lens of the Top Shops benchmarking program, the series explores the KPIs that set high-performing shops apart, from machine utilization and first-pass yield to employee engagement and revenue per employee.

Read More